Summary

On July 28, 2024, Venezuelans turned out to vote in large numbers despite more than a decade of systematic repression and human rights violations under President Nicolás Maduro.

Hours after polls closed, the Electoral Council declared that Maduro had been re-elected, with over 51 percent of the vote. The United Nations Electoral Technical Team and the Carter Center, which observed the elections, said the process lacked transparency and integrity, and questioned the declared result. The Carter Center said that the precinct-level tally sheets published by the opposition, which seemed to indicate that opposition candidate Edmundo González had won, were reliable and “authentic.” The Electoral Council failed to release the official tally sheets and did not conduct the required audits or citizen verification processes mandated by law.

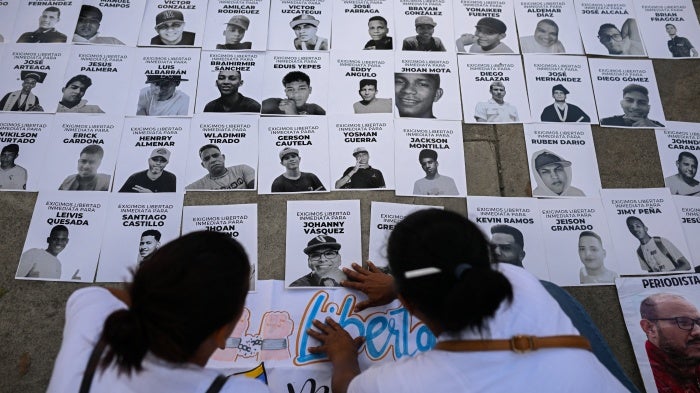

Thousands of protesters took to the streets in demonstrations, most of them peaceful, demanding a transparent and fair counting of the votes. They were met with brutal repression.

This report—based on 100 interviews with victims, their relatives, eyewitnesses, and members of human rights groups, and on analysis and verification of more than 90 videos and photographs—documents human rights violations committed against protesters, bystanders, opposition leaders, and critics during the protests and over the months that followed. It implicates Venezuelan authorities and pro-government armed groups known as “colectivos” in widespread abuses, including killings of protesters and bystanders, enforced disappearances of opposition party members and foreign nationals, arbitrary detention and prosecution of children and others, and torture and ill-treatment of detainees.

Human Rights Watch received credible reports of 25 killings during protests across the country immediately after the elections. Most of these killings occurred on July 29 and 30, with most victims being under the age of 40 and from low-income neighborhoods. Credible evidence gathered by Human Rights Watch points to the involvement of Venezuelan security forces in some of these killings. In other cases, “colectivos” appear to be responsible.

These “colectivo” groups played a key role in suppressing demonstrations. Security forces initially sought to control or disperse protests by setting up barricades, using tear gas, and carrying out arrests. When demonstrations persisted, “colectivo” members would arrive—often armed—to intimidate or attack protesters.

Since the election, over 2,000 people have been detained in connection with protests, political opposition activities, and human rights work. Many have been arrested for participating in demonstrations, expressing criticism of the government, or supporting the opposition. Prosecutors charged hundreds of people with broadly defined offenses, such as “incitement to hatred,” “resistance to authority,” and “terrorism,” which carry severe sentences of up to 30 years.

Those arrested have often faced proceedings riddled with abuses. Authorities have frequently denied arresting people they had in fact detained or refused to disclose the whereabouts of detainees to their relatives, subjecting them to enforced disappearances as defined under international law. This has forced families to search for their loved ones in multiple detention centers—and even morgues—for days or weeks. Many detainees have been held incommunicado and deprived of visits for extended periods, some from the day of their arrest. Most have not been allowed to see a lawyer of their choice, despite requests from them or their families, while others have never met with their court-appointed public defender while detained. Detainees have been repeatedly denied access to their legal case files. Many were charged in virtual and group hearings that further undermined their due process rights.

Security forces arrested Sofía Sahagún Ortíz, a Spanish-Venezuelan citizen, on October 23 when she was boarding a plane at the Caracas airport. The family’s lawyer went to the Attorney General’s Office and the Ombudsperson’s Office asking officials for information on her whereabouts, but authorities denied the request for information. In mid-December, she was allowed to call her family and told them she was being held in a police center in Caracas. In January, the Ombudsperson’s Office informed Sahagún Ortíz’s family that in December she had been taken before an anti-terrorism judge, in a virtual hearing, and that the following day she had been transferred to Helicoide, Venezuela’s Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional, SEBIN) headquarters, in Caracas. At time of writing, she remained detained, facing several charges, including “financing of terrorism.”

Venezuela’s Attorney General’s Office claims that roughly 2,000 people detained following the elections have been released. Many have been forced to sign documents prohibiting them from disclosing information about their arrest or legal proceedings. In some cases, they were also compelled to record videos stating that their rights were respected during their detention.

Security officers in black uniforms took Estuardo Pérez Olmedo (pseudonym), a community human rights defender, from his home in early August. They told him they were following a “presidential order.” Over four months, he was transferred between six detention centers, enduring harsh conditions, including lack of access to water, food, and medicine. Security forces pressured him to falsely accuse opposition figures of organizing protests. In November, he learned he was being accused of setting fires during protests that took place on July 29 and 30 near his home. He denied any involvement in these events. He was charged with terrorism and incitement to hatred. Upon his release in December, he was forced to sign a document saying that his rights had not been violated. The criminal investigation against him remains open.

The post-electoral crackdown has forced elected officials, local authorities, campaign coordinators, polling station workers, human rights defenders, and journalists to leave the country. Many are seeking protection abroad, where they face asylum systems in Latin America that are plagued with delays, and stalled resettlement proceedings to the United States.

A decade since Maduro took office, domestic and international efforts to protect human rights in Venezuela are at a critical juncture. While most governments have criticized Maduro’s power grab, repression in Venezuela has reached new heights.

Years of varying international and domestic policies towards Venezuela—from “maximum pressure” under the first administration of President Donald J. Trump in the United States to government and opposition talks supported by the Biden administration that help lead to the 2024 elections—have failed to produce a transition to democratic, rights-respecting governance. In the context of increased global crises, past failures risk future paralysis: a turning away from initiatives to protect rights in Venezuela and a normalization of grave human rights violations, unfair elections, and political repression.

The current Trump administration is seeking migration cooperation and the release of detained American citizens from Maduro, including through diplomatic engagement and sectoral sanctions. Some recent statements and decisions adopted by the administration show worrying indications that the US government intends to prioritize these goals over broader efforts to promote human rights and the rule of law in Venezuela. Given the diplomatic weight of the United States in the region and the increasing backlash against migration across Latin America, other governments are likely to adopt similar approaches, deprioritizing principled policies toward Venezuela. Simultaneously, Colombia and other countries bordering Venezuela may feel the need to seek Maduro’s cooperation on a varying range of issues, including security.

Maduro is likely to use such short-term cooperation to try to legitimize his power grab. That would only set the stage for increased repression in Venezuela and a new outflow of Venezuelans, with new refugees and migrants joining the millions of others who have left the country in the last decade.

Instead of giving up on human rights in Venezuela, governments in Latin America, Europe, and the United States should build on the admittedly insufficient results achieved so far. The July 2024 election and its aftermath deprived the government of any credible democratic legitimacy and helped spur renewed global condemnation of Maduro’s abuse of power. This is thanks in large part to brave efforts of Venezuelans who risked—and often suffered—grave human rights violations, including many whose stories are documented in this report.

A central issue is that, to date, foreign and domestic efforts have failed to make a dent in Maduro’s domestic carrot-and-stick incentives that reward abusive authorities and security forces, making them loyal to the government, while punishing, torturing, and forcing into exile critics, opponents, and even security force members who support democracy and human rights.

To disrupt these incentives, foreign governments should fully support existing accountability efforts against perpetrators of human rights atrocities in Venezuela—including by imposing carefully-designed targeted sanctions and supporting the continued work of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (FFM), established by the UN Human Rights Council, and the International Criminal Court (ICC), whose prosecutor is investigating potential crimes against humanity in Venezuela. This support also requires defending the work and independence of the ICC, particularly in light of recent Trump administration sanctions targeting the court.

They should also explore ways to encourage or pressure governments that assist Venezuela in its repression to end such activity. This includes the Cuban government, which according to evidence compiled by the FFM, has “trained, advised and participated in intelligence and counter-intelligence” with counterparts at Venezuela’s General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (Dirección General de Contrainteligencia Militar, DGCIM) and provided training to the SEBIN.

Foreign governments should also use their engagement with the Maduro government as leverage to secure verifiable, even if gradual or stepwise, improvements in human rights—particularly the release of people, both nationals and foreigners, who have been forcibly “disappeared” or arbitrarily detained.

Importantly, foreign governments should expand support for Venezuelan civil society groups, independent journalists, and others advocating for democracy and rights. They should also urgently expand protections for those forced to leave the country due to persecution and other forms of abuse. In particular, the administration of President Trump should reinstate key sources of support that were suspended as part of the United States’ larger rollback of foreign assistance. It should also consider reinstating the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and resettlement programs for vetted Venezuelans fleeing abuses in their country. Latin American and European governments should help address financing gaps and expand their efforts to protect Venezuelans who flee.

With 8 million Venezuelans abroad, the rights crisis in Venezuela remains arguably the most consequential in the Western Hemisphere. The region cannot give up on the plight of Venezuelans and their struggle for democracy and human rights.

Methodology

This report builds on Human Rights Watch’s prior reporting on post-electoral repression in Venezuela in 2024. It includes new evidence on human rights violations, as well as updates on cases Human Rights Watch reported on in the immediate aftermath of the elections.[1]

In researching post-electoral repression in Venezuela, Human Rights Watch interviewed 101 people, including victims, relatives, witnesses, human rights defenders, journalists, and other local sources. Many other relatives, witnesses, and others declined to be interviewed because they feared government retaliation. Human Rights Watch conducted phone interviews with sources in Venezuela between July 2024 and April 2025, and in-person interviews with Venezuelans who fled the country after July 28, 2024.

Most of those interviewed spoke to researchers on condition of anonymity. As a result, relevant citations omit details that could possibly lead to their identification. Certain details about cases or the individuals involved, including imagery (blurred or otherwise), have also been withheld when Human Rights Watch believed that publishing the information might put someone at risk.

Before each interview, Human Rights Watch informed participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and how the information would be used. We obtained verbal consent from each interviewee. They did not receive any compensation, benefit, or other incentives for speaking with us. When appropriate, Human Rights Watch provided contact information for organizations offering legal or counseling services.

Additionally, Human Rights Watch analyzed and verified 76 videos and 17 photographs connected to the post-election repression. These included imagery of people who had been killed and injured, or of protests or other relevant events found on social media platforms or sent directly to researchers by people close to the victims, organizations, and journalists involved. Where possible, researchers confirmed the exact locations where the photographs or videos were captured; used information such as shadows, weather patterns, and upload times to determine the time of day they were captured; and consulted with forensic pathologists, who analyzed visible injuries, and arms experts, who analyzed the weapons that were seen or heard in the content. Human Rights Watch has preserved the footage.

Human Rights Watch researchers also reviewed seven death certificates of people killed in the protests and other documentation related to arrests and criminal proceedings.

Background

A Decade of Unfair Elections

Weeks after Hugo Chávez’s death in 2013, his vice president and hand-picked successor, Nicolás Maduro, was elected president with 50.6 percent of the vote compared to 49.1 percent for opposition candidate Henrique Capriles, according to Venezuelan electoral authorities.[2] The Supreme Court of Justice (Tribunal Supremo de Justicia, TSJ) and the National Electoral Council (Consejo Nacional Electoral, CNE) rejected appeals filed by Capriles challenging the results.[3] Controversy over the results led to demonstrations and counter-demonstrations. Security forces used excessive force on protesters and carried out arbitrary detentions. At least nine people were killed and dozens injured.[4]

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled in 2024 that the Venezuelan government had compromised the integrity of the 2014 election by abusing state resources to favor Maduro and that in doing so, it had violated Capriles’ right to equal competition and Venezuelans’ right to freely choose their leader.[5]

After 16 years of legislative dominance by Chavismo—the political movement created by Chávez—the opposition coalition, Unitary Platform, secured a majority in the National Assembly in 2015.[6] But in 2017, Maduro convened a pro-government Constituent Assembly and granted it sweeping powers that extended beyond constitutional reform.[7] This move, which undermined the authority of the opposition-led National Assembly, triggered mass protests, with tens of thousands of Venezuelans taking to the streets to oppose the government’s actions.[8]

In 2018, Maduro declared victory in an early presidential election, marked by low levels of participation. The disqualification of numerous opposition candidates drove the opposition to call for a boycott of the elections.[9] The CNE reported that Maduro had secured 67.8 percent of the vote, followed by opposition candidate Henri Falcón with 21 percent.[10] The election drew widespread criticism for failing to meet international standards of fairness and transparency. Governments around the world rejected the results,[11] while observers documented irregularities.[12]

Prior to Maduro’s inauguration in early 2019, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans took to the streets again. Opposition leader and head of the National Assembly Juan Guaidó declared himself interim president during a mass rally.[13] Over 50 governments recognized Guaidó as the “legitimate president” of Venezuela,[14] but Maduro rejected calls for new elections.

In 2021, an independent EU electoral mission monitoring the November local elections reported that political opponents had been arbitrarily disqualified from running for office, that there had been unequal access to the media, and that lack of judicial independence and of respect for the rule of law had undermined the election’s impartiality and transparency.[15] The report laid out 23 recommendations to ensure free and fair elections in Venezuela. These included measures to establish transparent, non-political, and merit-based selection of judges and to abolish the comptroller general’s authority to strip citizens of their political rights through an administrative procedure arbitrarily used against political opponents. The report also recommended strengthening the CNE’s enforcement authority, especially in relation to the use of government resources in electoral campaigns and campaign coverage by state-owned media.[16]

The 2024 Election

On October 17, 2023, the Venezuelan opposition parties, allied under the Unitary Platform, and the Maduro government signed the Barbados Agreement as part of a negotiation that started in Mexico in 2021.[17] They agreed to honor political parties’ right to choose their presidential candidates and to hold a presidential election in the second half of 2024, among other election-related measures.[18]

The United States government, then under the Biden administration, agreed to temporarily lift certain sanctions on Venezuela in exchange for a commitment to hold free and fair elections.[19] The US also released Alex Saab, a Colombian businessman and close Maduro ally who had been indicted in the US for money laundering. However, the Maduro government’s failure to live up to its obligations under the Barbados Agreement prompted the US to reimpose some of the sanctions in January and April 2024.[20]

On February 28, 2024, the National Assembly signed a National Agreement outlining general principles, a proposed electoral schedule, and an expansion of “electoral guarantees” for the 2024 presidential election.[21] Members of the Unitary Platform were left out of the consultation process.[22] On March 5, 2024, the CNE announced that the presidential election would be held on July 28.[23]

In the lead-up to the election, Venezuelan authorities took renewed steps to undermine the fairness of the process. The government-controlled National Assembly replaced all 15 members of the CNE with government-aligned people. Authorities also arbitrarily arrested political opponents, disqualified opposition candidates, and replaced the leadership of opposition political parties.[24]

In late October 2023, Maria Corina Machado won a primary election organized by the opposition with more than 90 percent of the vote.[25] However, in January 2024, the TSJ upheld a June 2023 decision by the Comptroller’s General’s Office to disqualify her, as well as opposition leader Henrique Capriles, from running for office.[26]

Machado then sought to nominate Corina Yoris, a university professor, to run in her place, but the electoral authority blocked Yoris’ candidacy.[27] In March 2024, the electoral authority allowed Edmundo González, a former diplomat, to register for the Democratic Unity Roundtable (Mesa de la Unidad Democrática, MUD), a coalition of opposition parties.[28]

Repression ahead of the elections was severe, with authorities arbitrarily detaining 142 people between July 1 and 27, according to the local civil society organization Foro Penal.[29] Among them was prominent security expert and human rights defender Rocío San Miguel, who was detained in February 2024 and remained behind bars at time of writing.[30] Others detained included leaders of and people who worked or volunteered for Machado’s party, Vente Venezuela, such as her security chief Milciades Avila.[31]

Venezuelan authorities also harassed perceived opposition supporters, including by closing or fining restaurants or hotels used by Machado and González, and detaining people who provided logistical support, such as sound equipment, for their rallies.[32]

“Colectivos,” criminal groups, and other armed groups reportedly intimidated opposition candidates and voters during the electoral campaign, particularly in border and mining areas.[33]

In May, the CNE withdrew an invitation to the European Union to observe the elections, a move that contradicted the Barbados Agreement.[34] On July 17, in response to an invitation from the opposition, a group of European Parliament members agreed to send an electoral delegation to monitor the electoral process, but they were stopped upon arrival at the airport and deported.[35] Only two international election monitors were allowed into the country: the United Nations Electoral Technical Team and the Carter Center.[36]

Voter registration was also restricted. Authorities mandated resident visas to register to vote from abroad, leaving only 69,212 of nearly five million eligible Venezuelan voters living abroad registered.[37] And just two days before election day, the Venezuelan government closed its border with Colombia, where nearly three million Venezuelans live.[38]

Election Day

Venezuelans voted in the presidential election in large numbers. Over 59 percent of registered voters participated, despite a backdrop of intimidation and repression.[39] UN experts found the electoral environment was “largely peaceful” and “logistically well organized.”[40]

Observers, the media, and social media users reported restrictions on access to some polling stations as well as last-minute changes.[41]

Observers from the Carter Center also identified “ruling party checkpoints in the vicinity of voting centers,” known as puntos rojos.[42] In most cases, the checkpoints were used to record who had voted, according to the Venezuelan Electoral Observatory’s (Observatorio Electoral Venezolano, OEV) monitoring.[43]

Although the Carter Center said that voting took place in a “generally civil manner,” it also reported violent incidents linked to altercations or protests around polling centers, and intimidation by pro-government groups.[44]

“Colectivos” reportedly intimidated opposition voters and observers at polling stations in some parts of the country.[45] For example, multiple witnesses told Human Rights Watch that around 3 a.m., armed motorcyclists, who they believed to be “colectivos,” arrived at polling stations in San Antonio, Táchira state, on the border with Colombia, firing shots into the air to intimidate voters who had been queuing since early hours to vote.[46] Two witnesses said that initially, barricades of the Directorate of Strategic and Tactical Actions of the Bolivarian National Police (Dirección de Acciones Estratégicas y Tácticas de la Policía Nacional Bolivariana, DAET) blocked their access to get closer to one polling station, but between 6 and 7 a.m., DAET officers removed the barricades, allowing the motorcyclists to approach the station, and intimidate voters.[47]

The Aftermath

Six hours after polls closed, Venezuela’s CNE declared that Maduro had won the election with just over 51 percent of the vote.[48] The CNE did not release and still has not released the tally sheets from the election, nor conducted the audits or citizen verification processes required by law.[49] On August 22, the Electoral Chamber of the TSJ—which lacks independence from the executive[50]—validated the CNE’s results.[51]

The United Nations Electoral Technical Team and the Carter Center said the process lacked transparency and integrity and questioned the announced results.[52] The opposition said it collected around 85 percent of the total precinct-level tally sheets from the election, which according to the Carter Center were “authentic.”[53] The Carter Center reported that those tally sheets showed González had won decisively with approximately 67 percent of the vote, and described the results announced by the CNE as “statistically impossible.”[54]

Following the electoral council’s announcement on July 29, thousands of protesters took to the streets in largely peaceful demonstrations demanding a fair vote count. Only 7 percent of all post-election protests involved violence, according to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict (Observatorio Venezolano de Conflictividad Social, OVCS).[55] The OVCS also found that over 900 protests took place over the next 48 hours, most of them in low-income neighborhoods traditionally supportive of Chavismo.[56]

The government responded with what it called “Operation Knock Knock”[57]–an effort to intimidate, harass, and repress critics and protesters across the country, particularly in low-income areas.[58] Authorities established checkpoints, known in Venezuela as “alcabalas,” across the country and security forces stopped and often extorted people.[59] At the checkpoints and through random stops on the streets, security forces inspected people’s phones and other belongings.[60] High-level authorities, including Maduro, urged Venezuelans to report critics and opposition leaders through smartphone apps, such as the government-developed VenApp.[61] Security and intelligence agencies posted messages and arrest videos on social media to instill fear, using eerie music from the horror film A Nightmare on Elm Street and visual effects reminiscent of horror movies. The videos also displayed the text “Operation Knock Knock, no crying” alongside the logos of the Ministry of the Interior and security forces.[62]

“Colectivos” assisted in these efforts, repressing protests,[63] intimidating people in low-income communities,[64] and apparently marking the homes of critics and members of the opposition with intimidating graffiti.[65]

Between August and November, the government-controlled National Assembly also passed legislation severely restricting the work of civil society groups and criminalizing with up to 30 years in prison people who advocate for sanctions, whether targeted or broad, in Venezuela.[66]

On January 10, 2025, Jorge Rodríguez, president of the government-controlled National Assembly, swore in Maduro as president.[67]

Killings During the Protests

Human Rights Watch received credible reports of 25 killings in the context of protests. Researchers received these reports from independent local groups, including Foro Penal, Justicia Encuentro y Perdón, Monitor de Víctimas, and Venezuelan Program for Education and Action on Human Rights (Programa Venezolano de Educación Acción en Derechos Humanos, Provea), or discovered them on social media. The people killed included 24 protesters or bystanders, as well as one member of the Bolivarian National Guard (Guardia Nacional Bolivariana, GNB). Most were killed as protests peaked on July 29 and 30, 2024. Most—22 of the 25—were under the age of 40 and mostly from low-income neighborhoods.[68]

Eight cases were reported in Caracas District, mostly in the low-income neighborhoods of El Valle and Antímano. Seven occurred during the same protests in San Jacinto, Maracay, Aragua state. The remaining cases occurred in Bolívar, Carabobo, Lara, Miranda, Portuguesa, Táchira, Yaracuy, and Zulia states.

Venezuela’s Attorney General Tarek William Saab said on multiple occasions that 28 people had died “at the hands of violent demonstrators.”[69] He also claimed that the deaths could be attributed to groups supporting Edmundo González’s candidacy, known as “comanditos.”[70]

Evidence presented in this report implicates security forces, including the GNB and the national police (Policía Nacional Bolivariana, PNB) in some killings. In other cases, pro-government armed “colectivo” groups appear to be responsible.

Human Rights Watch found that in many cases security forces initially sought to control or disperse protests by setting up barricades, deploying tear gas, and carrying out arrests. When demonstrations persisted, “colectivo” members would arrive—often armed—to intimidate or attack protesters.[71]

Selected Cases

Rancés Daniel Yzarra Bolívar and Jesús Gregorio Tovar Perdomo (Aragua State, July 29)

Rancés Daniel Yzarra Bolívar, a 30-year-old civil engineer who worked in a food truck, took part in protests in the San Jacinto neighborhood, in Maracay, Aragua state, on July 29. He lived in a social housing complex that had recurring power outages. A relative of Yzarra Bolívar said that he had been hopeful about the elections and participated in the protests because of “frustration with the lack of change.”[72]

Jesús Gregorio Tovar Perdomo, 21, worked with his father at the local market in Maracay. His relatives described him as a calm boy who did not speak much.[73]

On the morning of July 29, people in the San Jacinto neighborhood of Maracay, a city approximately 80 kilometers to the west of Caracas, banged pots and pans from their homes, protesting a power outage and the announced electoral result.[74] At around 2:30 p.m., protesters took to the streets marching toward the Maracay Obelisk, a landmark in the city around 200 meters from the 42nd Parachute Infantry Brigade’s compound.[75] Human Rights Watch verified three videos of thousands of protesters around the Obelisk. Two of the videos, filmed from a high building, were posted to Facebook on July 29 and recorded between 1:45 and 3 p.m. based on shadow analysis. The third, estimated to have been filmed around 2 p.m., shows crowds singing the Venezuelan national anthem and waving flags.[76]

Dozens of people approached the military compound and called for soldiers to come out and join the protest, a witness said. A soldier asked them to leave. Some left but others stayed. About half an hour later, the GNB arrived.[77]

A video uploaded to Instagram by a journalist and verified by Human Rights Watch shows GNB officers arriving at around 5 p.m.[78] In the video, officers equipped with riot gear on motorcycles, accompanied by a riot control vehicle, advance down Avenue 2 West and form a blockade in front of the military compound. Protesters, some on motorcycles and others on foot, are seen protesting peacefully, chanting “freedom, freedom,” close to the entrance. Four other videos Human Rights Watch analyzed show people protesting peacefully near the same entrance.[79]

A six-minute video posted to Instagram almost half an hour later by a journalist and verified by Human Rights Watch shows a cloud of smoke coming from two locations in the vicinity of the military compound. A voice off-camera says it is 5:37 p.m. and that GNB officers are using tear gas to disperse protesters.[80] Human Rights Watch geolocated the video approximately 150 meters from the compound.

A journalist told Human Rights Watch that after the GNB attempted to disperse protesters, some threw rocks and burned police motorcycles in retaliation. In one verified video, protesters are seen throwing Molotov cocktails in the direction of the military compound.[81]

At approximately 6 p.m., a bullet hit Yzarra Bolívar on the left side of his chest, a relative said.[82] Human Rights Watch analyzed and geolocated four videos showing Yzarra Bolívar injured.[83] In one verified video, taken by a journalist at 5:50 p.m. and posted to Instagram 20 minutes later, two protesters are seen carrying Yzarra Bolívar to a location approximately 150 meters from the military compound. Other protesters are heard shouting “they killed him.” The video subsequently shows three other protesters carrying him to the back of a white van, which drives away.[84]

Yzarra Bolívar’s death certificate, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, says that he died of acute hemorrhagic shock due to the perforation of organs in his thoracic cavity.[85]

Human Rights Watch analyzed and geolocated a video sent directly to researchers showing another protester, Tovar Perdomo, who was severely injured in the same protest.[86] In the video, taken on Avenue Bolívar approximately 25 meters from the military compound, a group of protesters are seen frantically placing an unconscious man on a motorcycle. Three gunshots are heard and at least one uniformed man with a riot shield is seen in the background. The camera then zooms in on the man’s left waist to show a large open wound. A distinctive tattoo on his left forearm matches a picture of Tovar Perdomo sent to Human Rights Watch by a relative.[87]

The Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG) of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) reviewed a video of Tovar Perdomo’s wound and concluded that it was likely caused either by a high-velocity gunshot or a gunshot at close range.[88]

In another video uploaded to X on July 29, a shirtless man is lying still and face down on the ground on Avenue Bolívar, approximately 166 meters from the military compound.[89] A group of protestors, some on motorcycles and others on foot with one carrying a GNB riot shield seemingly to guard himself, move towards the shirtless man, trying to help him. A large group of GNB officers are seen approximately 135 meters away, at the intersection of the avenue and the military compound. The two videos appear to have been taken around the same time due to the presence of uniformed personnel and the matching clothing worn by one of the protesters. Human Rights Watch was not able to determine the identity of the man lying in the road.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed evidence regarding the death of José Antonio Torrents Blanca, a First Sargeant in the GNB, during the same protest. On July 30, GNB Commander General Elio Estrada announced the death of Torrents Blanca on X, calling him a “victim of the violence unleashed by fascist groups.”[90]

Human Rights Watch verified a video sent directly to researchers showing GNB officers carrying a seemingly unconscious person in a military uniform. A voice off-camera says, “They got Torrente.” The video was filmed in what appears to be a parking lot approximately 50 meters in front of the brigade, with smoke plumes in the background matching the approximate location of fires seen in other videos.[91] A lightly blurred video uploaded to X on July 30 shows a group of GNB officers putting the unconscious person on the back of a motorcycle in the same location shown in the previous video.[92] The exact time of both videos and the circumstances of the officer’s death could not be determined.

Human Rights Watch received reports that four other people died from injuries inflicted during the same protest in Maracay: Anthony David Moya Mantía, Jesús Ramón Medina Perdomo, Gabriel Ramos Pacheco, and Andrés Alfonso Ramírez Castillo. Local human rights groups who documented the cases told Human Rights Watch that they all apparently died from wounds caused by firearms.[93]

The National Survey of Hospitals, a group of healthcare workers that monitors health issues in Venezuela, reported that about 50 people injured in the Maracay protests arrived at three hospitals between July 29 and August 1.[94] Human Rights Watch analyzed and geolocated four videos in which eight people can be seen bleeding from injuries or being carried by protesters.[95] Some of the patients, both those injured or killed, had gunshot wounds, the group said.

Two people who knew the victims, and a witness present during the protest, said that many protesters were wounded by shots coming from inside the military compound.[96]

Human Rights Watch verified a video recorded by a local journalist who was shot in his stomach and right leg during the protests.[97] In the video, recorded in front of the military compound, facing the entrance, three gunshots are heard. After the final shot is heard, the journalist lowers the camera and no longer films the protest scene. With the camera lens pointing at the ground, he stops by a tree, where several people approach him, appearing to express concern for his well-being. The journalist told Human Rights Watch the video was filmed at approximately 5:30 p.m.[98]

Walter Loren Páez Lucena (Lara State, August 4)

Walter Loren Páez Lucena, a 29-year-old father of two, joined a group of protesters in Carora, Lara State, on July 30.

The night before, protesters on motorcycles gathered outside the local office of the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela, PSUV), as seen in three videos posted to Instagram and X in the early morning of July 30.[99] In one video, a protester climbs to the first floor of the building to remove an election poster of Maduro as others cheer. Another protester is seen spray-painting “Hasta cuándo?” (“Until when?”) on the wall of the building.

The next day, protesters gathered peacefully near Francisco de Miranda Avenue, close to Ambrosio Oropeza Square. A journalist and a witness said that the demonstration remained peaceful, a claim supported by six videos posted to Facebook verified by Human Rights Watch showing protesters waving flags, banging pots and pans, and chanting.[100] A photograph posted at 12:58 p.m., captioned with a time of 11:40 a.m., shows hundreds gathered peacefully near the square.[101]

According to police records reviewed by Human Rights Watch, Páez Lucena was shot and injured at approximately 2 p.m. close to the local office of the PSUV, five blocks from the Ambrosio Oropeza Square.[102] Several sources, including an eyewitness present at the scene, confirmed the approximate time of the events.[103]

His mother and cousin reported to the police that the protest had remained peaceful until the gunfire began.[104] A witness also said that protesters reacted only after Páez Lucena was shot and the GNB had left. “Imagine you’re protesting peacefully, and [from the PSUV office] they open fire on you while the GNB just stands there watching. That enrages you,” he said.[105]

A video posted to Facebook by Carora TV in the afternoon, consisting of four clips, shows protesters peacefully gathered while dozens of GNB officers with riot shields stand in a line a few meters away outside the PSUV office.[106] Shadows suggest this was filmed at around 2 p.m.—the time that Páez Lucena was shot. The second clip in the video shows GNB officers in riot gear and at least eight motorcycles with drivers dressed in black wearing black helmets. In the third clip, a man’s watch reads 12:50 p.m. as protesters on motorbikes drive approximately 100 meters from the office on Riera Silva Street. Another video posted to Instagram in the evening and filmed at the same location between 3:30 and 4 p.m., according to shadow analysis, shows protesters, some running, moving west. A small fire is burning in the middle of the road.[107]

As the situation escalated, videos showed worsening conditions outside the PSUV office in the afternoon and evening, before nightfall at 7:30 p.m. In one video a lone GNB officer seems to be trying to talk with some protesters, some with their faces covered, as another protester a few meters away throws objects towards the direction of the office, shattering nearby windows.[108] A video posted online by the state governor of Lara shows protesters throwing objects at GNB officers.[109]

Testimonies, news reports, a firefighter’s report reviewed by Human Rights Watch, and videos and photographs posted to Facebook, Instagram, and X indicate that protesters set fire to the PSUV office, damaging the building and at least a dozen motorcycles.[110]

Multiple videos circulated in the days following, most prominently videos shared by a reporter with the state-owned broadcaster VTV CANAL. These show several injured people in civilian clothing, and one being attacked with kicks, stone blocks, and a machete.[111] Human Rights Watch could not match the location of these videos to the PSUV office and could not confirm that they are from this incident.

After being injured, Páez Lucena received initial treatment at the Policlínica in Carora but was sent home. As his condition worsened, he returned to the clinic, where doctors recommended immediate surgery, but due to financial constraints, his family transferred him to the public hospital, Hospital Central Universitario ‘Antonio María Pineda,’ in Barquisimeto—an hour and a half away by car—where he underwent surgery on August 3.[112]

His partner, María de los Ángeles Lameda Méndez, was arrested that night as she left the hospital to buy medical supplies for Páez Lucena. According to statements to the police from Páez Lucena’s mother and cousin, a prosecutor informed Paéz Lucena at around 1 a.m. that his wife had been detained. At around 7 a.m. on August 4, Páez Lucena died in the hospital.[113]

Police records and a death certificate indicate that Páez Lucena died of sepsis caused by peritonitis originating from a gunshot wound.[114] An independent forensic expert reviewed Paéz Lucena’s autopsy and concluded that the wounds could have been caused by a weapon firing ammunition coinciding with the type of bullet shells found at the scene.[115]

Before his death, Páez Lucena told his mother that hooded men with covered faces had been shooting from the roof of the PSUV office.[116] According to the police’s ballistic analysis bullet shells were found on the upper floor of the building, making it safe to say that the shooting occurred from there.[117]

Lameda Méndez was released in late December but remains under investigation for alleged terrorism and incitement to hatred.[118] A source close to the family told Human Rights Watch that Lameda Méndez did not participate in the protest held on July 30.[119]

Carlos Oscar Porras (Miranda State, July 29)

On July 29, Carlos Oscar Porras also known as “Bigote,” a soccer coach and father of two, participated in a protest in the town of Guarenas in Miranda State.

A journalist who covered the protests in Guarenas on July 29 and 30 told Human Rights Watch that demonstrations began spontaneously at around 10:30 - 11 a.m. on the 29th and were peaceful.[120] People banged pots and pans in low-income neighborhoods of Guarenas. The protesters initially gathered along the Guarenas-Guatire Intercommunal Avenue but later moved through the city, reaching areas such as Trapichito, Menca de Leoni, and La Vaquera, where Porras protested, according to his aunt.

According to the journalist, at around 6 p.m. GNB officers began intimidating protesters in La Vaquera in an effort to disperse them.[121] A video sent to and verified by Human Rights Watch shows a white light armored vehicle with GNB markings turning on to Calle Oeste leading to La Vaquera as a group of people on motorbikes continue to drive on the main road.[122] As the vehicle approaches, a smoke cloud consistent with tear gas is visible near the protesters. The protesters flee while at least one throws an object in the direction of the armored vehicle. In the video, a man wearing gray pants and a white shirt runs from behind a tree. Porras’s aunt identified the man as her nephew.[123] His clothes also match those Porras is seen wearing in another video.[124] The low position of the sun in the sky and illuminated headlamps of the armored vehicle suggest it was recorded around 6 p.m. When the security force vehicle approaches, the sound of a detonation can be heard in the background.

In another video posted to X on July 29 at 9:27 p.m., recorded at night from an apartment building on the same street, protesters are seen confronting security forces and throwing Molotov cocktails.[125]

A third video sent directly to researchers, filmed from a high floor of an apartment building in La Vaquera at night, shows a man in clothes matching the gray pants and white shirt worn by Porras walking slowly north along Calle Oeste along with a few other protesters nearby. A group of security forces are seen in the middle of the road surrounded by riot shields 170 meters north of Porras, close to the main road.[126] A shot is heard eight seconds into the video, the video flashes back to the protester who is now on the ground. At 0:24 of the video, a brief flash of orange light is visible near the shields, followed by a gunshot sound. A voice in the video says: “Look, they are shooting.” At 0:38, another louder shot is heard, and the same voice exclaims: “They shot ‘Bigote,’ they shot him.” Given the distance between security forces and protesters at the time of the shooting, Human Rights Watch determined that the shots were not fired from handguns or less-lethal weapons in this incident.

Human Rights Watch could not confirm if Porras was the person referred to in the video, although the nickname matches. Another video posted to X on July 30 shows a man, identified by his aunt as Porras, lying on the ground.[127] Some people attempt to treat a wound on his body by ripping open his shirt.

Isaías Jacob Fuenmayor González (Zulia State, July 29)[128]

Isaías Jacob Fuenmayor González, 15, left his home in San Francisco, Zulia state, late in the morning of July 29 to practice a dance with his friends for a friends’ upcoming 15th birthday party, his sister told Human Rights Watch.[129] On his way home, she said, Fuenmayor González joined friends who were participating in a demonstration near the Mathías Lossada High School, which had served as a polling station. A video sent to researchers and verified by Human Rights Watch shows Fuenmayor González walking among protesters, midway between the dance rehearsal site and his home.[130] The video was filmed late in the day as indicated by light in the sky fading to the west.

A journalist who was present told Human Rights Watch that Bolivarian National Guard (Guardia Nacional Bolivariana, GNB) members on motorbikes repeatedly rode into the crowd to try to disperse the protest at different times during that afternoon.[131] Human Rights Watch verified two videos that, in line with the journalist’s report, show GNB members using their motorbikes to disperse protesters.[132] By analyzing shadows, Human Rights Watch found that one of the videos, posted to X at 6:35 p.m., was recorded around 4:10 p.m. The journalist also said that some protesters threw rocks at the local office of the PSUV, located in front of the high school.[133]

The journalist, local media, and human rights groups say that “colectivo” members attacked protesters after the GNB’s initial clash with demonstrators.[134] Some time after 7:30 p.m., a bullet hit Fuenmayor González in the neck. Two videos filmed at night, which Human Rights Watch verified and geolocated to a corner of the high school, in front of the PSUV local office, show a boy carrying a clearly injured Fuenmayor González to a motorcycle.[135]

He was taken on the motorcycle to the nearby Doctor Manuel Noriega Trigo Hospital, where he died. His death certificate, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, indicates that he died due to blood loss caused by a gunshot wound to his neck.[136]

“I want justice for my brother,” Fuenmayor González’s sister told Human Rights Watch. “He was a child who did not deserve to die, a child who was just beginning to live.”[137]

Anthony Enrique García Cañizalez and Olinger Johan Montaño López (Caracas District, July 29)

On the afternoon of July 29, Anthony Enrique García Cañizalez, a 20-year-old student, left his home in El Valle, Caracas district, to bring food to a family member in the Supreme Commander Hugo Chávez Maternity Hospital, his aunt told Human Rights Watch.[138] As he was returning home, García Cañizalez encountered a protest near the Abigail González School, which had served as a polling station.

Olinger Johan Montaño López, 23, a barber from El Valle, took part in another protest that same day, close to the Simoncito Libertador School, according to a Facebook video geolocated by Human Rights Watch, approximately 750 meters northeast of the Abigail González School.[139] Montaño López was passionate about music. He composed and performed his own songs under the artistic name “Saffary,” according to his posts on social media.[140] “It is better to die in battle than to die in misery,” Montaño López posted on his social media that day.[141]

Human Rights Watch verified three videos filmed northeast of the Abigail González School, around Bolívar Square, that show GNB members dispersing the protest, including by throwing tear gas or smoke grenades, and shooting kinetic impact projectiles from riot guns.[142] In one of the videos, filmed at night, a person identifying themselves as a journalist, says that it is 7:32 p.m. (nighttime began at 7:14 p.m. that day). Protesters are seen throwing what appear to be rocks at security officers, as the security officers throw what appear to be tear gas or smoke grenades, and fire unidentified types of weapons in another direction off camera.

Two videos geolocated by Human Rights Watch just 200 meters northwest of the Abigail González School, filmed at night, show a group of people carrying an injured person, whom Human Rights Watch identified as Montaño López, and a group of people around another injured person on the road nearby.[143] A video shared on social media platforms shows a shirtless man covered in blood as a group of people pick him up.[144] García Cañizalez’s aunt identified the man as her nephew.[145] Human Rights Watch geolocated the video and confirmed it had been filmed in the same location as the other two videos.

García Cañizalez’s aunt told researchers he was shot at around 8:30 p.m. on his way home, 400 meters away from his house.[146] Montaño López had stopped replying to messages around 8:40 p.m., a source said.[147]

García Cañizalez died that day at Coche Hospital. His death certificate says that he died due to massive internal hemorrhaging caused by gunshot wounds.[148] “He was a young boy, with a zest for life, which was taken away from him,” his aunt said.[149]

Montaño López was also taken to Coche Hospital, where he died. His death certificate says he died due to penetrating thoracic trauma caused by a gunshot wound.[150]

Aníbal José Romero Salazar (Caracas District, July 29)

On July 29, Aníbal José Romero Salazar, a 24-year-old construction worker, known to his friends as “Pimpina,” took part in a protest in Carapita, a low-income neighborhood in Antímano, Caracas.

Human Rights Watch verified two videos filmed in quick succession posted to X at 4:43 p.m. and 4:53 p.m. These show protesters on Intercommunal Avenue, 300 meters southwest of the Carapita metro station, peacefully chanting and banging pots and pans, while passing motorbikes honk their horns. In one video, a group of men are standing at a bus stop and a nearby structure.[151] Using weather data, Human Rights Watch confirmed that the videos were filmed between 2:30 p.m. and when they were posted.

A third video posted to TikTok at 5:31 p.m. on July 29 shows hundreds of protesters by a nearby pedestrian bridge filmed that afternoon.[152] Dozens of protesters can be seen throwing objects at police officers in dark uniforms and others with yellow vests are shielding themselves and running away. Other officers appear to be firing their weapons at protesters.

Around 7 p.m., a bullet hit Romero Salazar on the right side of his forehead. A photograph posted to X at 7:45 p.m. on July 29 and reviewed by Human Rights Watch shows this wound.[153] He was about 230 meters from the protesters on Intercommunal Avenue.

Human Rights Watch reviewed an audio message sent by a witness to a local human rights organization.[154] The witness, who said he was at the protest with Romero Salazar, said that when Romero Salazar was injured, police officers from the Directorate of Strategic and Tactical Actions (Dirección de Acciones Estratégicas y Tácticas, DAET) were shooting firearms at protesters near a local church.[155] A video uploaded to TikTok and taken approximately 100 meters south of where Romero Salazar was shot shows an armed person wearing dark clothing with white letters on his back, consistent with DAET uniforms.[156]

A video posted to YouTube on August 2 filmed from a nearby building, which Human Rights Watch verified, shows the 21 seconds before Romero Salazar was shot and some seconds following.[157] Romero Salazar is outside the church with a group of protesters, holding what appears to be a homemade shield. A gunshot is heard, and Romero Salazar falls. Another video filmed in the same location, which was shared on X at 7:35 p.m. on July 29, shows protesters carrying a wounded Romero Salazar.[158]

The witness, whose audio Human Rights Watch reviewed, said that police officers did not allow protesters to take Romero Salazar to the hospital.[159] A video filmed after dark shows Romero Salazar lying wounded in the back of a truck that is not moving.[160] Eventually protesters were able to take him to the nearby Pérez Carreño Hospital, where he died.

During a news conference on July 31, Maduro showed a social media post that referred to Romero Salazar’s death and said it was “fake news.” Maduro claimed that Romero Salazar had confessed that his death had been faked, and as proof, he showed a video of a man stating that his own death was simulated.[161]

However, Human Rights Watch established that Maduro’s claim that Romero Salazar was not dead is demonstrably false; the name used by the man in the video Maduro showed, and the location at which he claimed the incident happened, did not match Romero Salazar’s case. A local human rights organization that assisted Romero Salazar’s family also confirmed that the person in the video shown by Maduro is not Romero Salazar.[162]

Yorgenis Emiliano Leyva Méndez (Miranda State, July 30)

On July 30, Yorgenis Emiliano Leyva Méndez, 35, participated in protests by motorcyclists against the electoral results in Ambrosio Plaza, Miranda state. The protest in Guarenas was largely peaceful, a media worker who covered the protest told Human Rights Watch. “The most violent thing I saw was people tearing down electoral propaganda from Maduro and burning it,” they said.[163]

Human Rights Watch verified a video of the protest taken at 4 p.m., according to its caption, and posted an hour later to Instagram.[164] The video shows a group of people chanting peacefully and carrying flags on the Guarenas-Guatire Intercommunal Avenue, 7.5 kilometers from Plaza Bolívar. Later, the protest moved toward Guarenas, the media worker said. Witnesses said, and a video reviewed by Human Rights Watch showed, that at around 5:50 p.m. a group of people on motorbikes yelling and blaring their horns were protesting around Plaza Bolívar.[165] In the video Leyva Méndez is seen on a motorcycle among the group.

The square was guarded by municipal police and armed men whom local people described as belonging to the “colectivo” Los Tupamaros, according to a media worker who covered the protest.[166] That afternoon pro-Maduro mayor Freddy Rodríguez had published a post on Instagram saying that “revolutionary forces” were “activated” to “defend” the city.[167] The previous day, a group of at least three unidentified men had thrown a Molotov cocktail in the city’s main square, Plaza Bolívar. Human Rights Watch analyzed and geolocated a video of the incident.[168]

Around 6:30 p.m., a bullet hit Leyva Méndez near Plaza Bolívar. His death certificate, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, indicates that he suffered internal hemorrhaging from a gunshot wound that lacerated his femoral artery.[169]

Human Rights Watch verified a video that shows Leyva Méndez wounded, his clothes stained with blood, being carried by two people and placed on a motorcycle, approximately 100 meters from Plaza Bolívar, where the Mayor’s Office building is located.[170] In the video, people are heard saying that the shot came from the nearby Mayor’s Office building. A journalist who covered the protest also said that people were shot from there.[171]

Enforced Disappearances and Pervasive Abuse in Detention

While the exact number remains unclear, over 2,000 people have been detained in connection with protests and political opposition since the July 28 elections.

According to the local group Foro Penal, at least 2,062 people were arrested between July 28 and December 31, with the largest number of detentions taking place between July 28 and the first two weeks of August.[172] Maduro said in early August that 2,229 people, who he described as “terrorists” and “criminals,” had been detained.[173]

While the vast majority of arrests took place between July and August, arbitrary detentions continued as the protests waned, especially in the days immediately before inauguration day when Foro Penal documented roughly 50 arbitrary arrests.[174]

Maduro and Attorney General Saab have repeatedly said that those arrested were responsible for violent acts, terrorism, and other crimes.[175] However, Human Rights Watch has found evidence that people were detained for what should be protected activities such as participating in protests, criticizing the government, or taking part in political opposition, and were then detained arbitrarily or pursuant to proceedings that did not afford meaningful due process.

Enforced Disappearances

In most of the cases Human Rights Watch documented, security forces did not show detainees an arrest warrant at the moment of their arrest; and several people were detained by hooded men who failed to present themselves as members of security forces. Relatives often learned of the arrests only through witnesses, acquaintances with ties to security forces, or anonymous tips.[176]

Authorities often denied the arrests had happened or refused to provide information on detainees’ whereabouts to relatives and others, in what amounted to enforced disappearances under international law.[177]

In addition, judges frequently failed to rule on habeas corpus requests in a timely manner or denied them on unreasonable grounds, such as claiming that relatives bore the burden of identifying the particular branch of the security forces responsible for the arrest.[178]

Relatives looked for their missing loved ones in multiple detention centers, and even in morgues, for days or weeks.[179] Often, they were only able to confirm the detainees’ whereabouts through other prisoners or because prison officers accepted belongings they brought for their family member—which many saw as a tacit acknowledgement that the person was detained in that prison.[180] Yet in early April, Foro Penal said there were still 62 people whose fate or whereabouts remained unknown.[181]

Rafael Tudares Bracho

Hooded individuals intercepted Rafael Tudares Bracho, Edmundo González’s son-in-law, on January 7 when he was taking his 7- and 8-year-old children to school. According to a written account by the family shared with Human Rights Watch, the hooded men violently pulled Tudares Bracho from his vehicle and left the children on the street.[182]

Mariana González, Tudares Bracho’s wife, undertook multiple efforts to locate him. She visited detention centers in Caracas and its surroundings, but authorities denied her requests for information. At one of these centers, a guard allowed Mariana González to leave clothes for Tudares Bracho. Yet when she returned, officials said that he was never held there. On one occasion, security officers told her that Tudares Bracho was held in the Rodeo I prison, but when she arrived at the prison, guards denied he was there.

In February, González learned that Tudares Bracho had been brought before a judge on January 10 and charged with treason, conspiracy with foreign governments, and criminal association, in “complicity” with Edmundo González. However, in early March authorities told her the hearing had been held on February 18, more than a month after the detention.

Mariana González learned that authorities assigned Tudares Bracho a public defender, despite his family’s efforts to secure a lawyer of their choice. According to González, the public defender was not present at the hearing where Tudares was charged, and authorities refused to share his name with the family.

“Being my father’s son-in-law is not a crime,” González wrote.

Sofía María Sahagún Ortíz

Security officers arrested Sofía María Sahagún Ortíz, a Venezuelan-Spanish citizen, on October 23 when she was boarding a plane at the Caracas airport directed to Madrid.[183] Sahagún Ortíz’s family said she texted her husband saying she had made it through passport control. Her relatives learned the next day that she had not been allowed to board the plane, but they were not informed of what happened to her next. Her family has repeatedly asked Venezuelan authorities to look for her and disclose whether she has been detained.

After she was disappeared, police officers repeatedly appeared at her family’s home and harassed relatives and acquaintances asking questions about the family, her husband told Human Rights Watch. Her husband and children moved out of their house and, days later, fled Venezuela.

On October 30, the family’s lawyer went to the Attorney General’s Office and the Ombudsperson’s Office asking officials to investigate Sahagún Ortíz’s case.[184] Prosecutors refused to open their own investigation, the family’s lawyer told Human Rights Watch. According to judicial documents reviewed by Human Rights Watch, prosecutors transferred the case to the Scientific, Penal, and Criminalistic Investigative Service Corps (Cuerpo de Investigaciones Científicas, Penales y Criminalísticas, CICPC), a branch of the police charged with carrying out forensic investigations.[185]

On December 19, 2024—that is, 57 days after her arrest—Sahagún Ortíz was allowed to call her husband and her brother. She told them that she had been detained at the airport on October 23, and that she was being held in the National Police’s Center for Protection and Control of Detained People, in El Valle, Caracas.[186]

The next day, her lawyers visited the police center to deliver her toiletries, food, and clothes. Police officers at the center said she had been transferred but did not say where and gave her lawyers the personal items that Sahagún Ortíz was carrying the day of her arrest.

On January 31, 2025, the Ombudsperson’s Office informed Sahagún Ortíz’s family that on December 19 she had a virtual hearing before an anti-terrorism judge, and that the following day she had been transferred to Helicoide, Venezuela’s Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional, SEBIN) headquarters, in Caracas.

On February 3, her lawyers went to the Helicoide to ask about her. An authority informed them that she was being held in that detention center, but was not allowed to receive visits, make phone calls, or hire a lawyer. In early April, she was allowed to see a visitor for the first time.

At time of writing, she remained detained, facing several charges, including “financing of terrorism.”

Nahuel Gallo

Nahuel Gallo, 33, is a first corporal in the Argentine Gendarmerie—a federal force—who worked at the Los Libertadores border crossing, between Argentina and Chile.[187] In December 2024, Gallo planned a trip to Venezuela to visit his wife, María Alexandra Gómez, who is Venezuelan, and their two-year-old son.

Initially, Gallo planned to arrive in Venezuela in August on a commercial flight from Panama City, Gómez said. Yet the flights were cancelled after Venezuela cut ties with Panama due to criticism regarding the elections. Gallo eventually decided to fly to Colombia and cross the border by land. “He was very excited about the trip. It was the first time in his life that he was leaving Argentina and taking an international flight,” Gómez told Human Rights Watch.

On December 8, Gallo crossed the Colombian exit checkpoint in Cúcuta in a taxi. When he arrived in Venezuela, he texted Gómez saying that Venezuelan officials at the border wanted to interview him. “We didn’t see anything strange about it. It seemed like a fairly normal procedure to enter a country,” she said. Gómez did not hear back from him for a couple of hours. At 11 a.m., he called Gómez from the taxi driver’s phone, saying that Venezuelan authorities were going to interview him again. He also said that he “had no more money.” The taxi driver later told Gómez that men in a black car with a General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (Dirección General de Contrainteligencia Militar, DGCIM) logo had taken Gallo.

In December, Attorney General Saab said that Gallo had been charged with conspiracy, terrorism, financing terrorism, and illicit association for belonging to a group that “attempted to carry out a series of destabilizing and terrorist actions.”[188] In January, Maduro publicly commented on the case, claiming that Gallo had plans to kill Vice President Delcy Rodríguez.[189] Yet, to date, Gallo’s family has not received information from authorities about any court hearings, nor on where he is being held.

On January 2, Venezuelan media outlets published some photos and a video of Gallo wearing a blue prison uniform. Gómez believes the photos were taken inside the Rodeo I prison. But when she arrived at the prison, guards told her that Gallo was not held there.

“I live in anguish and despair,” Gómez said. “I sleep with the phone on my chest in case someone calls to give me information about my husband.”

Despite multiple requests, the Argentine government has not been allowed consular visits or been informed about Gallo’s whereabouts.[190]

Incommunicado Detention and Charges of “Terrorism” and “Hatred”

Many detainees, including 33 cases documented by Human Rights Watch, have been held in incommunicado detention for days, weeks, or even months, in violation of international human rights standards.[191] While most detainees appear to have been allowed to receive visits, some detainees have been prohibited from receiving visits since the moment of their arrest.[192]

Most detainees have been denied the right to legal representation by a private lawyer of their choice, even when they or their families have explicitly requested one.[193] They have been appointed a public defender, but some never spoke to their defender while detained. They have also been consistently denied access to their case files.[194]

Authorities have used two laws that allow draconian penalties to carry out many of the detentions.[195] In particular:

The 2017 Law Against Hatred, which was enacted by the Constituent Assembly, imposes sentences of 10 to 20 years for anyone who publicly “promotes, encourages, or incites hatred, discrimination, or violence.”[196]

The 2012 Law Against Organized Crime and Terrorism Financing imposes sentences ranging from 25 to 30 years for terrorist acts intended to intimidate a population or committed with the aim of “severely destabilizing or destroying the fundamental political, constitutional, economic, or social structures of a country or an international organization.”[197]

Human Rights Watch documented several cases where detainees have been charged in virtual hearings with judges in Caracas, sometimes in groups, which undermines defendants’ right to access a hearing where the evidence and arguments against them are analyzed in an individualized and fair manner.[198] Such group proceedings are inappropriate because they make it harder for judges, prosecutors, and public defenders to adequately assess or present evidence and arguments pertaining to individual cases.

As of April 7, Foro Penal reported that 896 people the group described as “political prisoners” remained behind bars.[199] The Attorney General’s Office reported on March 3 that 2,006 people arrested in relation to the post-July 28 events had been released.[200] According to the office, these releases resulted from a review of pre-trial detention which, under Venezuelan law, judges can replace with less restrictive measures such as house arrest, periodic court reporting, and prohibitions on leaving the country or attending certain meetings.[201]

However, the people released from detention continue to be under criminal investigation. A person released in December told Human Rights Watch, “I am out of jail now, but to them, I am still a terrorist. Every day I fear they will come and lock me up again.”[202]

Additionally, people who have been released and their lawyers have said that many of those released were required to sign a document saying they would not disclose information about their case or arrest and, in some cases, to record a video indicating that their rights were respected during their detention.[203]

Many of those released say they have been required to appear before courts in Caracas, which handle cases involving the crime of “terrorism.”[204] Many people released said they missed the required appearances because they lacked the means or money for the long journey to the capital.[205]

Torture, Ill-Treatment, and Prison Conditions

The human rights organization Provea documented 2,224 victims of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment in 2024, including beatings, lack of medical care, and food deprivation. The organization reported an 88.1 percent increase in such cases compared to 2023, particularly in prisons and police stations after July 28. Provea also recorded 9 cases of torture involving 60 victims, most of whom were “political prisoners” held in Rodeo I prison.[206]

Human Rights Watch documented 12 cases of ill-treatment, some of which may amount to torture. Particularly serious incidents entailed beatings, electric shocks, asphyxiation, and solitary confinement.[207] The targets were most often individuals who are actual or perceived critics of the government, and in several cases those inflicting the abuse sought to extract information about opposition members or force confessions regarding alleged involvement in violent acts.[208]

Detainees and relatives of people detained told Human Rights Watch that in some cases people were subjected to electric shocks and asphyxiation with bags.[209] Two individuals who were detained between July and January reported seeing burn-like marks on the ribs and arms of other detainees.[210] The mother of a detained 15-year-old boy said that her son was subjected to electric shocks, which, she believed, caused him to suffer seizures.[211]

Human Rights Watch also documented the use of punishment cells. Five former detainees told Human Rights Watch that guards placed them—or threatened to place them—in punishment cells commonly known as “little tigers”[212] (tigritos in Spanish)—tiny, overcrowded and dark cells where detainees are held in isolation for several hours or even days.[213] One detainee said he slept standing up due to the lack of space, with around 30 people packed into a 2 x 3 meter area.[214]

A detainee described a cell known as “Adolfo’s bed” (la cama de Adolfo in Spanish) in Tocorón prison, “a kind of garbage closet” no bigger than “a washing machine box” where he had to always remain crouched. “It’s a hole,” he said. “It only has a door. It’s completely dark, so you lose track of time. If you need to go to the bathroom, you have no choice but to do it right there.”[215] Another referred to being stripped of his clothes and placed in a punishment zone in Rodeo I.[216]

Some detainees and their families told Human Rights Watch that detainees were beaten and subjected to other physical abuses by security forces, both during transfers and at detention centers, leaving visible injuries such as bruises, broken bones, and fractures.[217] Some detainees reported seeing guards beat detainees’ hands with their batons through the bars of cells. Others mentioned witnessing the “mata chivo,” a blow to the back of the neck that stuns or knocks someone unconscious, or punches to the upper central part of the abdomen, just below the rib cage.[218]

Some detainees said that security officers forced them to strip in public when they received uniforms, especially during transfers to Tocorón and Tocuyito prisons, and beat and insulted them as they changed clothes. Their heads were shaved.[219]

Former detainees described prison conditions marked by overcrowding, poor access to water, food, and basic health services.

In September, the Venezuelan Prisons Observatory (Observatorio Venezolano de Prisiones, OVP), a human rights group, estimated that given the size of the cells and the number of detainees held in them, each detainee had less than 1 square meter of personal space to sleep and move inside their cell.[220]

Food and water quality was poor across multiple detention centers and the OVP reported that some detainees in Tocuyito prison had as little as two glasses of water per day.[221] Detainees told Human Rights Watch that they had been served spoiled food. Others, including one person who lost over 40 kilograms in five months, suffered stomach issues and malnutrition.[222] In other centers, detainees relied on family members for food.[223]

From July to November 2024, the Committee for the Freedom of Political Prisoners in Venezuela (Comité por la Libertad de los Presos Políticos, CLIPPVE) reported that in several prisons, authorities prohibited families from providing medication to detainees.[224] They also failed to inform relatives about their love one’s health issues.[225]

At least four people who were detained after July 28 died in custody, including two members of Vente Venezuela. In two cases, the deceased detainees were held in Tocuyito prison, in Carabobo. According to information provided by local organizations and media outlets, the causes of death were related to a lack of timely medical care and ill-treatment.[226] People who died in custody include:

Jesús Manuel Martínez Medina, a member of the opposition party Vente Venezuela, who was detained on July 29 in Anzoátegui state. He died on November 14 in a hospital after both of his legs were amputated due to necrosis. According to information provided to Human Rights Watch, he had diabetes.[227]

Jesús Rafaél Álvarez, who was arrested along with his wife on August 2 in Bolívar state after the protests. He died on December 12 while detained in Tocuyito prison. According to the OVP his 20-year-old son was never allowed to visit him, as only women were permitted to enter the prison. The son told the OVP and media outlets that his father had been healthy but was beaten in prison, which ultimately led to his death.[228]

Osguald Alexander González Pérez, who was detained with his son on August 1 in Lara state after the post-election protests. He died on December 15 after months of detention at Tocuyito prison. According to the OVP, he had hepatitis, which was not treated promptly.[229]

Reinaldo Araujo, the leader of Vente Venezuela in a parish in Trujillo state, who was detained on January 1. According to information shared with Human Rights Watch, he had leg issues and heart problems from high blood pressure. He died on February 24, after being transferred to a hospital.[230]

Conditions in the Main Detention Sites

Aragua Penitentiary Center, known as Tocorón (Aragua State); and Judicial Internment Center of Carabobo, known as Tocuyito (Carabobo State)

Tocorón is a maximum-security prison located in the south of Aragua state, known for having become the stronghold of the criminal gang Tren de Aragua, a criminal group that controlled the prison and used it as headquarters.[231] Tocuyito is the main prison in Carabobo state. In 2023, Venezuelan authorities said they had dismantled “all [the] criminal structures” in these prisons and would physically restructure the detention sites.[232] Human rights organizations still have doubts and concerns about this restructuring.[233]

In early August 2024, Maduro announced on X that “all fascist criminals” were going to be sent to Tocorón and Tocuyito.[234] Without notifying their relatives, or considering that many lived far away, Venezuelan authorities have transferred hundreds of prisoners to these facilities.[235]

The transfers were conducted in heavily guarded buses.[236] A detainee who was held in Tocuyito alleged that security forces subjected him to “brutal treatment” and psychological abuse during his transfer. The detainees were handcuffed with their hands behind their backs, he said, and authorities forced them to lift their arms—causing him significant pain, he said. They also told them they were “terrorists” and “filthy ‘guarimberos’”—a pejorative term used to describe those who participate in opposition protests.[237] Another detainee transferred to Tocorón stated that while they were on route, unaware of their destination, the bus stopped and was surrounded by armed security forces. “We all thought they were going to kill us,” he said. After making them wait for a while, an armed officer stepped onto the bus and, laughing, said, “Chill out, we’re not going to kill you—at least not yet.”[238]

Families and released detainees reported overcrowding, restrictions on phone calls and visits, and inadequate detention conditions.[239]

Boleíta Control Center or Zona 7 (Caracas District)

Originally a building for administrative purposes, Zona 7 is a detention center of the national police (Policía Nacional Bolivariana, PNB) that houses more than 400 detainees in 14 to 16 cells, according to OVP.[240] Detention conditions can vary significantly within the facility, with cells in better condition allocated to those who can afford to pay.[241]

Detainees say the basement, known as “underworld” (inframundo in Spanish), is the worst part of the detention center. Two described how the walls “cry” from humidity and overcrowding.[242] According to the OVP, as of January 2025, approximately 90 detainees were being held in this cell without ventilation, sunlight, or bathrooms.[243] Detainees held in the basement do not have access to a bathroom and people who were held there said that the cells contain human waste.[244] “I’d rather stay one month in Tacorón than one day in Zona 7,” a detainee who was held in both detention facilities told Human Rights Watch.[245]